Wish I'd Known...

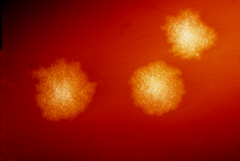

C.difficile colonies - something you don't want too much of in your gut. Thanks to Wikipedia.

I love science. I really do. I love the pursuit of new knowledge, the asking of the questions, and the deep curiosity at the base of it all.

What if?

I wonder why?

How does this work?

And I truly am grateful to have lived long enough to now know what I wish I’d known before. I mean who knew that those wonderfully cleansing antibiotic soaps would one day be seen as contributing to antibiotic resistance? Or that the amazing productivity and yields coming from today’s American agriculture due to new chemicals and seed strains may be coming at the expense of human health and vitality?

Our mothers believed the advertising – that smoking was good for you, so how were they supposed to know that smoking and drinking during pregnancy was a two person pursuit that was particularly bad for the one growing inside?

There’s the conundrum. We know what we know based on the current knowledge available to us. And I’m convinced that science is pursued with the best of intents – but rarely with a complete understanding of the unintended consequences resulting from those intents.

The intent was cleanliness and sanitary surfaces with antibiotic soaps. Who could have predicted that too clean could be a problem – that we needed some of those bacteria in our lives? And, ok, I’m not going to presume that tobacco had any intent other than increased sales, but I do believe early on even the companies had no idea how addictive and deadly their product proved to be.

So the point of all of this is to say, “Sorry, kids.”

Recent studies and articles now show that antibiotic use in very young children can transform the good bacteria living in the gut, leading to struggles with obesity, and metabolism – or energy/fatigue. And these are long-term impacts.

Long after the ear infections and sore throats are gone, the gut flora and fauna are altered without announcing the change in any perceptible way other than a tendency to put on weight easily.

My children were young in the late 1980s, before the words “epigenetics” or “gut genome” were thrown around in conversation. When my kids got sick, we went to the doctor, where we commonly heard, “Well, I’ll give you this antibiotic which may not help, but it certainly won’t hurt.”

It was a comforting idea that, as parents, we were doing something for our feverish, sick kids. And it was wrong.

I don’t blame the pediatricians and family practice docs for not being microbial scientists. They, too, were doing what they thought best.

What I’ve learned is that all science, all new knowledge needs to be recognized for what it is. It’s the latest, the most recent best knowledge. It’s part of the progression of unraveling this marvelous experience of life on this planet. But it’s not final. It will never be final.

So I propose that all science – all new knowledge – come with a warning label that says, “Don’t blame your parents. They didn’t know better because we just learned this ourselves.”